Guardian partners with Caribbean GIS to track chikungunya in the Caribbean

Everything about chikungunya is painful. Even the virus’ name comes from a Kimakonde word describing the contortions of one suffering severe joint ache. Fever, rash, cramps, headache, nausea and fatigue are just some of the symptoms of the mosquito-borne illness.

Nor is tracking the spread of the disease across the Caribbean any easier. English-language reports on the virus’ transmission at the sub-regional level are put out by public health authorities, including the Caribbean Regional Public Health Agency (CARPHA), the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) and the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

But keeping up with information from all of these sources can be time-consuming, especially if you just want to keep an eye on the spread of the disease in your own country, or get a sense of the broader regional picture.

“It’s easy to point a finger and criticise but I thought it would be better to actually demonstrate that something better could be done,” said Vijay Datadin, founder and lead consultant at Guyana-based Caribbean GIS.

Datadin should know. He’s made a career of applying geographic information systems (GIS) to the complex interrelationships between human and natural resources.

“When I looked at the outputs of CARPHA, PAHO and even the CDC, I thought they could be enhanced. Specifically, PAHO is putting out data reports in PDF format, which is really less than ideal. Where there are maps, they could be made more informative and charts would help citizens understand the situation more easily. I felt it could be done better, because they’re still doing it in the old-fashioned way.”

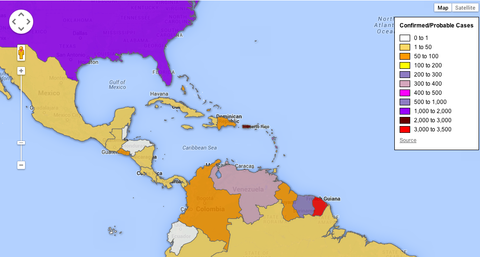

Datadin is co-lead on a new open data project that aims to fix two major pain points associated with the “old-fashioned way” of sharing public health data. First, as a one-stop resource for official chikungunya numbers, the online tracker seeks to cut out the hassle of having to check multiple websites, in order to get the latest collated statistics on the spread of the virus.

The second pain point is how chikungunya transmission data are presented by the three leading public health agencies in the Americas. Modern public health sites like HealthMap aggregate news reports in real-time and push notifications to subscribers, filtering by relevance based on geolocation. They are built with responsive design to dynamically adapt to different form factors such as mobile devices, tablets and desktop screen displays. Plus they are mobile-optimised for lightweight browsing, and social-friendly for maximum user engagement.

By comparison, the regional websites are less impressive. The CDC website provides a static map showing countries where local transmission has been documented, and says that “chikungunya case counts are publicly released every Wednesday.” PAHO provides a weekly report every Friday afternoon of Chikungunya counts for most countries of the Americas and a static map showing countries with local and imported cases. CARPHA provides a weekly update of Chikungunya counts every Monday. The CARPHA site also has an interactive map with a useful timeline feature illustrating the progression of the disease through the region and mouse-over info boxes showing the number of cases in a country.

The region's public health services could learn from the open data approaches that are becoming the expected standard for providing public information, Datadin said.

“Around the world, public organisations are no longer simply publishing their data in PDF format or static maps but in open data formats and interactive maps. The value in doing it this way is that data scientists, researchers and other interested parties are then able to not just see the data but actually use it,” Datadin said.

His latest project, a joint initiative of Caribbean GIS and the T&T Guardian’s new media unit, brings to traditional public health reporting the transparency of open data formats and the interactivity of data visualisation. The end-product is an online map-based chikungunya tracker that makes it easy for anyone with Internet access to follow the regional diffusion of the disease, using public health data extracted from official sources. The tracker is online at http://www4.guardian.co.tt/map-chikungunya-caribbean.

Data for the map and charts on this page were extracted from PDF reports published by PAHO, reformatted and combined with a GIS base map. On the Caribbean GIS Health site the map is accompanied by other charts and timelines that provide historical context and make each country’s demographic situation easier to grasp at a glance.

The improved Chikungunya dataset is also made freely available as a Fusion Table so that other researchers, students and citizen scientists can view, filter or merge with other data with just a browser, or download for further analysis.

Mapping Caribbean Crime

The joint project isn’t Datadin’s first foray into data journalism. In 2003, Datadin founded Red Spider, a small web development startup, which today maintains the Guyana Crime Reports, an open data tracker for several categories of serious crime in Guyana. The website is part news aggregator, part crowd-sourced citizen journalism platform.

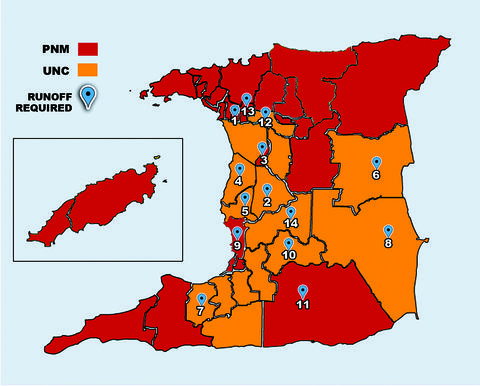

In 2013, Guyana Crime Reports collaborated with the now-defunct Bullet Points, an earlier open data journalism project involving Guardian’s new media desk, which tracked intentional homicide as well as deaths caused by shootings involving police officers. Datadin, who was at the time working on Guyana Crime, worked with Bullet Points to develop a GIS-powered map of 384 murders in its 2013 dataset.

“I feel that the Caribbean is better off when its citizens are better informed,” Datadin said.